Lupus

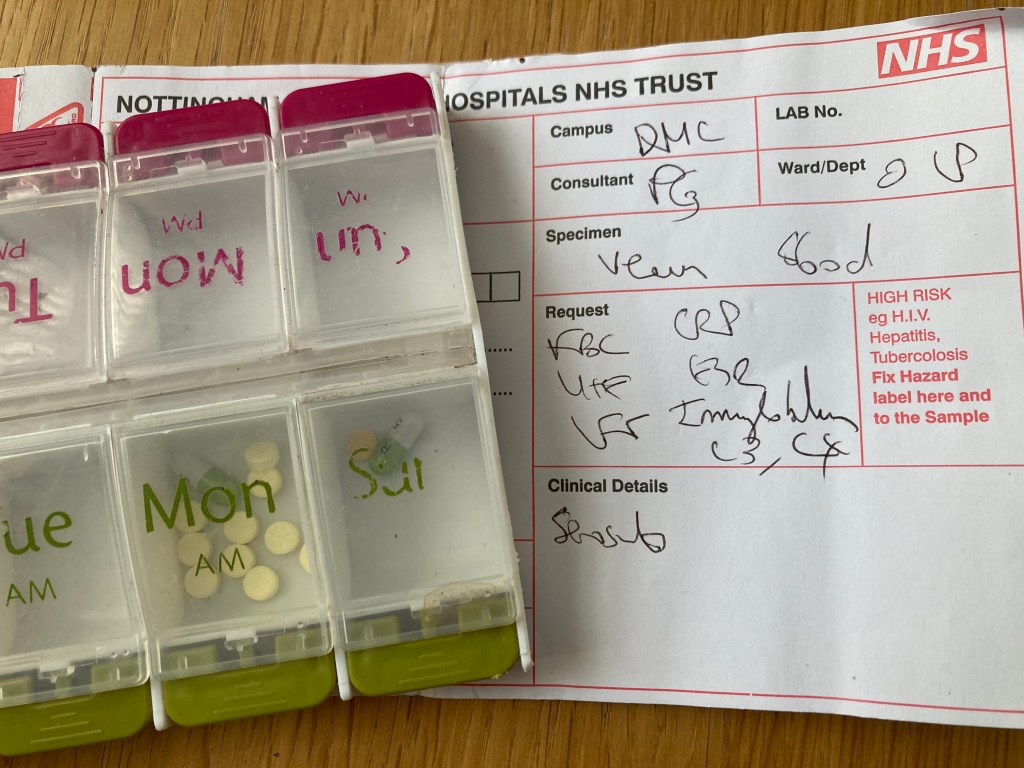

I have an auto-immune condition. It’s not a disease, but something has gone wrong with my body’s immune response, and it has started to attack healthy cells. These conditions are more common than you think: arthritis and multiple sclerosis are perhaps the best known and long covid is now considered to be one. The condition I have is probably systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus), but a slightly unusual form. I’ve never had the distinctive butterfly rash, or the joint pain; what I do have is sirositis, where from time-to-time the fluid around my lungs and heart fills up making it hard to breathe and pushing up my heart rate (this is known as a flare). For reference when I wrote the first draft of this post my heartbeat was 102bpm as I sat typing. Pre-condition my resting heartbeat was much nearer 60bpm.

I also feel like pants and get fatigued a lot.

And there’s a mental health factor. One of the side effects is “general discomfort, uneasiness, or ill feeling”. And because it’s serious (potentially fatal in my case), the drugs I’m on are also pretty hardcore. These include steroids and chemotherapy drugs that suppress my immune system to try and prevent my body attacking itself. All the drugs have potential physical side effects, but the steroids also play around with emotions including both mood enhancement and mood depression, and, in the most extreme cases, suicidal thoughts.

I therefore have a cocktail of factors that mean on any given day I might wake up in the morning and feel overwhelmed, exhausted, or in just a negative mood.

- Is it the malaise associated with the condition?

- Did I just do a little bit too much exercise yesterday?

- Is it the side effect of steroids?

- Is it just the depressing realisation that this condition is frankly a bit shit?

- Is it just that I spend a large part of my life waiting for a the condition to flare up?

- Is it just that it can be hard to tell the difference between the very early stages of something minor like a cold and the start of a flare?

- Is it just that I’m heavier & less fit than ever?

- Am I just having a bad day/ stressed about a deadline or something in my personal life that would be an issue for any normal person?

And, obviously, the answer is probably a bit of all of the above. I have a real medical condition, there are tests and measures and literally fluid showing up in the wrong places in X-Rays, but this is also a condition with a massive mental dynamic. The flares can be brought on by stress, or infections (or just randomly is seems), but day-to-day I sometimes have to ask the question “Am I ill right now, or am I stressed about the possibility that I might be ill, or have I got so used to being ill that this is my new baseline?” Sometimes I can tell – if I get out of breath walking up a flight of stairs, it’s very likely to be physical, but most of the time it’s a bit of a judgement call.

I’m three years into this condition and now, finally, the medication appears to be working and the worst of the flares now seem to be passing. I’m categorically not writing this because I’m asking for sympathy or an easy time and I know this could be a hell of a lot worse. I’m writing this because there’s something really important about expectations.

I expect to feel rubbish.

A lot.

And I feel rubbish.

A lot.

On some days it might be 100% physical, on others it might be 100% mental. To some extent, it doesn’t matter what the cause is, I experience both as real. Part of the challenge is that I need to try and get as fit as possible without over-exerting myself and my baseline of ‘normal’ exercise is completely out of step with my new normal (also a form of stress). I also think that for me, part of the problem is that the systems can be like suffering with depression: I have a lot of fatigue and that influences how I approach my day. I will find a way through this. It will be okay.

I needed to write the section above so that I can be clear about my starting position. I’m not going to write about ‘snowflakes’ or suggest that student wellbeing is a made up phenomenon. I don’t think I can be any clearer that I believe that the mental causes of illness are as just as real as the physical ones. If you read this next section as me mocking or laughing at our students with wellbeing problems, with all-due-respect, you’re bringing that to the interpretation, not me.

Psychogenic illness

I’ve come across two pieces about psychogenic illnesses, and perhaps as importantly mass psychogenic illnesses. The first is in David Robson’s (2022) book “The Expectation Effect (podcast)”, website, and the second is from Tim Harford’s Cautionary Tales Podcast.

I think that the notion of placebo effect is now well recognised, even if we’re not sure how to use it in medical practice. There is, however, also the opposite effect: the nocebo effect. The nocebo effect happens when patients read the list of possible side effects from drugs and experience those effects. There have been proper blinded studies where patients in the control group have suffered side effects from a drug, even when it’s physically impossible for them to have come into contact with it. In other words, a psychogenic illness.

For me, even more interesting is the idea of mass psychogenic illnesses: whole groups can become ill through the same process. There’s a good argument that most of the reported side effects associated with statins are caused by the nocebo effect. It’s possible that lots of people who take the drug have read the labels about side effects and have individually suffered them, but I think there’s a stronger case that the side effects arise because there is lots of folklore circulating about the side effects.

One really interesting example of mass psychogenic illness is the Havana Illness. In the late 2010s, staff based in the US embassy in Havana started to report illnesses associated with high pitched noises. Gradually, it appears that more and more people heard about this phenomenon and began to report the same experience. The US Government began to investigate possible toxins, sonic weapons and radio wave weapons etc. I think that there’s a credible argument that it was a mass psychogenic illness. It’s perhaps telling that the US Government invested a lot of energy into finding these secret weapons rather than accepting that their staff may have been experiencing something we historically (and unhelpfully) called mass hysteria.

Is the Student Wellbeing Crisis a Mass Psychogenic Illness?

No

We are seeing a growth of mental illness and concerns about wellbeing amongst our student population. I believe that it’s a real phenomenon and growing at a very fast rate. I understand that mental health problems amongst university students are associated with socio-economic factors such as familial income, I don’t believe that it’s just a problem of the worried well. And students do have legitimate reasons to be concerned over issues such as individual debt, future employment and existential issues like the future of their planet. Arguably it has been exacerbated by the Covid-19 and post Covid world: students have missed out valuable opportunities to grow and to develop their self-confidence and coping strategies.

But Can We Learn Anything From Mass Psychogenic Illnesses?

Yes

The sector is under a huge amount of pressure about wellbeing. We don’t want our students to be struggling with mental ill health, but we’re also under scrutiny from the Government, from regulators and from parents. I think though that we face a huge problem. We are inevitably pushed towards treating every case as the worst possible case scenario. Brutally, if we don’t, there’s a risk that following an incident such as a student suicide, anything less can look callous and cold.

But there’s a paradox, Robson, puts it succinctly: “Worst case thinking doesn’t prepare you, it promotes the worst case” (Robson, 2022). In other words, if we prepare all students for the risk of serious mental ill health, we plant the idea that higher education providers are centres, or the even the root cause of serious mental ill health. Some students are seriously at risk of depression, self-harm or worse; we do need to plan for the worst and communicate options to them. Nonetheless, are we at risk of priming ALL students into believing that they’re going to become mentally ill?

I’m clearly not a mental health expert; I’ve put together my personal experience and something that I’ve been thinking about for a while. You are welcome, of course, to be critical. I’m also not responsible for explaining my institution’s practices to grieving parents. Of course, the sector must respond to a real phenomenon. I think I’m suggesting that we are just careful about how we communicate to students, particularly early in their experience at university. I know that institutional mental health specialists will be careful to not put the frighteners on students during induction talks, but there’s a wider issue in the day-to-day experience of new students: the border between excitement and anxiety is potentially very small. Entering a lecture theatre for the first time can be a pretty overwhelming experience. For many students, university is a place that they’ll deal with heart break, stress, even mundane issues like colds for the first time without their parents offering immediate reassurance.

We have choices in how we frame these issues in our discourse with students. We can create environments that disempower them: “you need to speak to a counsellor”, or we can remind students that these sensations are normal and encourage them to at least recognise that possibility.

We clearly need to provide the mental health back stop and students need routes to professional support, but treating every student as the potential worst case scenario disempowers them and swamps our systems. We need to be very careful that our everyday interactions with students demonstrate to them their capacity to cope and even thrive in new environments. In classrooms students need to be reminded that learning can be hard and it’s normal to struggle with new concepts. It’s always worth acknowledging the nerves, but reminding students that they may be experiencing excitement, not anxiety. It’s also okay to share your own stories of struggling and your own doubts.

How to do it

There’s an idea that I think deserves a post all of its own, but it fits perfectly. It’s from Felten & Lambert’s excellent “Relationship Rich Education: how human connections can drive success in college” (2020).

They describe an example from a large economics course in California (slightly re-formatted by me).

“In the light-touch study, a faculty member sent each student in a high-enrollment introductory economics course two personalized emails during the semester with the purpose of providing tailored information about

(1) the student’s performance in the course to date,

(2) strategies and approaches that help students learn in the class, and

(3) the availability of the professor and other resources to support the student’s success in the course.

Students who received these emails scored higher on exams, homework, and final course grades than students in the control group who did not. Some students who received these emails even responded to express gratitude to the professor for caring enough to email or to say that they would try to work harder for the remainder of the semester.” (Felten & Lambert, pg 90).

Yes this approach is a big task, but for most institutions, it’s one where we could make better use of our IT to make it manageable.

Student wellbeing is a real issue. It requires proper support and a high quality backstop. However, we need to build student capacity to cope with the new and unfamiliar through the way that we communicate expectations and scaffold the early higher education experience. We also need to be careful not to create the impression that all students are on an inevitable conveyor belt to a wellbeing crisis.