At the time of writing (Summer 2023), the UK higher education sector has implemented learning analytics fairly widely (albeit in fits and starts). We have been using ‘engagement’ or ‘student success’ analytics since the early 2010s. Truthfully, the technology has proven to be good at identifying students at risk of early departure, but finding ways to reduce early departure has proven far more difficult. This doesn’t mean that the approach is wrong, but it does mean that the technology is not a short cut to fixing students’ problems (and possibly never will be).

Whenever I’ve run workshops on learning analytics, I tend to use the following definitions:

‘Learning Analytics is about collecting traces that learners leave behind and using those traces to improve learning’ (Duval, E., 2012). I like using Duval’s definition, but I think it comes out of the thinking at the time. This was written around the time of ‘peak MOOCs’, it could well be describing the algorithms supporting intelligent question sets.

In the UK, the sector has tended to focus differently, learning analytics is much more likely to be used in the domain of student engagement or student support. This was described by Sclater as learning analytics for success: the ‘early identification of students predicted to be at risk of failure or withdrawal’ (Sclater, 2017, pg. 35).

In the past couple of years though, the sector has taken learning analytics down a different route. Instead of seeking to reduce the risk of early departure, a new focus has arisen about the notion of wellbeing analytics. I’ve therefore added a new definition in my presentations. I now say that learning analytics includes systems: ‘… that enable HEPs to identify students who have a heightened risk of developing poor mental wellbeing. This facilitates more proactive signposting or intervention before students’ needs become more serious’ Peck (2023)

And I think that there are some really serious issues to consider.

What are my concerns?

The first issue is a simple one – what is wellbeing?

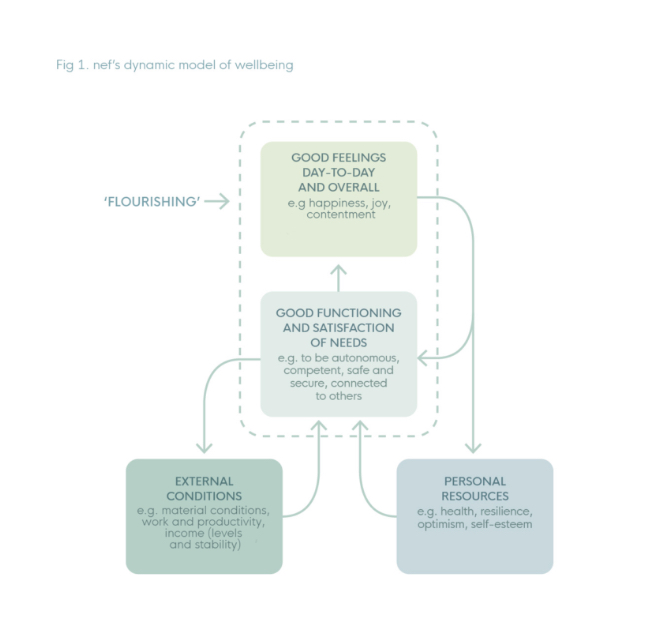

On one level, it’s very self-explanatory: it simply describes how individuals, groups or society at large is coping with the day-to-day travails of life (the New Economics Foundation use the word ‘flourishing’). I think it’s important that wellbeing is understood as existing within a system. Wellbeing is dependent upon an individual’s internal resources and their supportive networks interacting with the challenges that day-to-day living presents. Wellbeing problems can therefore arise from issues in the wider society, but also because the individual has particular difficulties or lacks specific resources. I’m not seeking to blame here – this ties to notions such as grit and growth mindset that I think may be useful for explaining the post-Covid engagement crisis.

Figure 1 – the New Economics Foundation model of wellbeing

For learning analytics then, wellbeing means the degree to which a student is coping with the challenges of the educational, social and societal systems they operate within.

I’m aware that one of the challenges here (like with most forms of learning analytics), is that we tend to look at the issues from the perspective of the individual. It’s perfectly reasonable to argue that some students cope (and even thrive) with the stresses put upon them, but others don’t, and therefore wellbeing should be individualised. However, what if the system is broken? What if the problems of student wellbeing are caused by a crappy, badly-funded system? That’s not a problem of the individual, that’s a problem of the system. Higher education policy is probably outside the remit of anyone reading this post; we can only do the best that we can within an imperfect environment.

The second definitional issue is that we’re probably mostly interested in students who aren’t coping. It’s perhaps a little like attendance monitoring systems, where we’re not really interested in attendance, but absence. We are interested in students with ‘poor’ or ‘low’ wellbeing not really those who are flourishing

There’s a further consideration. Wellbeing analytics might not be about the whole student’s wellbeing, but about component parts. For example, the UK Jisc code of practice for wellbeing and mental health analytics suggests ‘Possible applications cover a very wide range: from screen-break reminders to alerts when a student appears to be at risk of suicide.’ This also has huge implications: I suspect that a relatively large number of students would consider that they have wellbeing problems in the course of a normal year, suicidal thoughts are far less prevalent, but of course far more serious in consequence.

The first issue of wellbeing analytics is that it’s bloody ambiguous. The early developers’ definition of learning analytics used pretty tight definitions – ‘how many students passed or failed a question?’, ‘what’s the relationship between resource use and successfully completing summative tests?’ or ‘why does everyone quit our MOOC at week 5?’. Similarly, I’d argue that, whilst it’s flawed in many respects, student success analytics has some clear metrics – ‘did the student pass the course or did they drop out early’, ‘what grades did they achieve?’.

For wellbeing analytics to be valuable and meaningful, we need clear metrics about what precisely we are measuring.

I move to writing about wellbeing metrics next.

Pingback: The problem with wellbeing analytics (& what we need to do to fix it) (part 2 – metrics) – Living Learning Analytics Blog